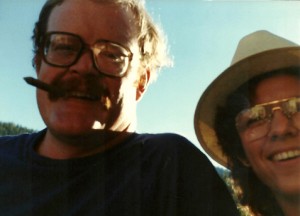

In the late 1970s, Grady Myers was an artist at the Boise, Idaho Newspaper.

I was a young features editor. We went separately to an office party where people were supposed to dress like they did in the ’60s. My costume was a giant 45-rpm record. Grady wore fatigues and told entertaining stories about serving in the Vietnam War. I was fascinated. In those days, the military used a lottery system to draft young men. Most guys I grew up with had college deferments or high draft lottery numbers, and managed to avoid Vietnam. If they’d gone, they rarely talked about it.

I asked Grady if I could write down his stories. He said yes. I stocked the fridge with Old Milwaukee, bought a cassette recorder and got him talking. When I transcribed the tapes, I thought: This is like “M*A*S*H,” only set in Vietnam instead of Korea. Of course, not all of Grady’s stories involved humor, or even black humor. People died. People suffered. He suffered. But Grady recounted even the saddest parts as if telling an adventure story. His descriptions were those of an artist and a reporter: detailed with sights, sounds, and smells.

Grady served as an M-60 machine gunner in the U.S. Army’s Company C’s 2nd Platoon, 1st Battalion, 8th Brigade, 4th Infantry Division in late 1968 and early 1969. His Charlie Company comrades knew him as Hoss. To put my interviews with him in context, I learned more about what the Vietnamese called the American War. Grady had been “in-country” for a few months in 1968-’69, at the war’s height, when the U.S. had half a million troops in Vietnam. Desperate to keep the troop pipeline filled, the Army was taking people with physical and mental shortcomings who would normally have been unacceptable. That included Grady, an extremely nearsighted 19-year-old. Grady and I produced a manuscript that I typed on an electric Smith Corona and he illustrated with drawings. We also produced a marriage, our son, Jake, a divorce and an enduring friendship. The manuscript stayed in a series of closets and packing boxes. Jake served in the U.S. Air Force as both of his grandfathers had done before him.

When Grady was in his late 50s, he began thinking about the war a lot. Thanks to information he found on the Internet, he learned things he’d never known, including that he had participated in a military operation dubbed Wayne Grey. After decades of separation from his Army buddies, he discovered that Charlie Company had started to hold reunions. But he was never able to attend. Health problems had confined Grady to a wheelchair and, eventually, to a nursing home bed. He needed something to occupy his mind. S o we dusted off the book manuscript. He propped himself up so he could see his computer and created new artwork, this time collages made from Vietnam photos he discovered online. He painstakingly reviewed the manuscript, adding details and added more profanity, too, because that’s the way the soldiers talked. When I deleted some cuss words with the argument that they interfered with the narrative flow, his reaction was a grudging OK, so long as I didn’t girl-ify the story with “heck” and “darn.”

Grady vividly remembered many experiences in Vietnam. The emotions stuck to his brain like the red tropical dirt stuck to his body. He called it a time of intensive living. He told his wartime stories—always complete with sound effects (his helicopter imitation was second to none)—without rancor or regret. He did sometimes come down hard on himself. After he’d reviewed his behavior as described near the end of this book, he e-mailed me to say, “I’m finding I don’t like Spec. Myers very much.” I replied that I liked the young soldier a whole lot. He was so … human.

Grady was a man of contrasts with big talent, small ego, strong language, and a gentle spirit. His tough constitution was legendary, as was the disregard he showed for his health. A futile war left him in pain, yet he was proud of his military service. He was well acquainted with depression, yet all of his life he made people laugh. He once looked at a picture of himself in Vietnam, in which his camouflaged helmet accentuated his strong jaw and big eyeglasses. “I was just a kid,” he said. “Hell, we were all just kids.” Now, Grady’s kids have kids. When he died in 2011 at the age of 61 from diabetes and other maladies, I thought it was time to share his stories.

The result is a poignant and sometimes funny memoir, “Boocoo Dinky Dow: My short, crazy Vietnam War.”

~ Julie Titone, Co-author with Grady C. Myers of Boocoo Dinky Dow: My Short, crazy Vietnam War

www.shortcrazyvietnam.com/

We are very grateful to Julie for sharing her story with Comes A Soldier’s Whisper, where we are all connected.

Facebook Veteran Tributes :

www.facebook.com/ComesASoldierswhisper

#VietnamWar #history #Books #Veterans